“My uncle would put us all in his big blue van and take us to North Tower Cinema or take us to Mayfair, starting early in the morning at 9 a.m., then we’d all pay for one movie. We’d all go see a movie together and then after that, for the rest of the day, we were just sneaking into different movies,” remembered director, filmmaker and educator Marquise Mays.

“We’ve always had that right and I think growing up, especially as I became like a preteen teenager that’s when Black kids specifically started kind of being policed at movie theaters,” he added. “So they kind of ruined my movie-watching experience. But when I got to UW for undergrad, I think I fell in love with the practice of filmmaking there.”

It was during his time as an undergrad at UW-Madison that Mays found his niche: Documentaries.

“I was a journalism major my first year … and I always had this idea that I was gonna be like a broadcast reporter, I wanted to be on screen really bad, so I wanted to take a lot of multimedia classes and stuff like that and the first class I really took that first year was video production class and we made like a documentary,” Mays explained. “And I was just like, “Wait, I think I’m really good at this thing.’ I think it was really natural for me to ask questions, and for me to follow someone and for me to kind of just be immersed in their story and cutting their story together.”

Mays recalls his professor awarding accolades to him and his teammates for their film, confirming on an academic level that, yes, he was good at this thing.

However, despite this, Mays remained a journalism student. It wasn’t until later, in the wake of Tony Robinson’s murder on Madison’s east side, that he began struggling with the field of journalism and its intrinsic linkage to the notion of objectivity.

“It was really hard to be objective,” Mays said. So, with the help of his advisors, Mays was allowed to take classes in both journalism and filmmaking, exploring the process of making what had so enthralled him in his youth and as such relieved some of the hindrances that an objectivity-driven field like journalism presents.

“There was the grand opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture that we got the opportunity to go,” Mays explained. [So] I went to Carla, who is in control of it, and was just like, ‘Hey, can I bring the camera and can I just record this? I think it’s really important that we record this moment of how it was, how we felt.’ And it just became a moment of like, at this point, now I’m just archiving. So my love for filmmaking came from loving movie-watching … but it also came through research and archiving and having an interest in really uncovering what it meant to see ourselves on screen.”

Throughout the archival process, Mays is always “moving in truth,” hence his moniker “Truth Seeker & Truth Speaker.”

“I argue with myself all the time when I’m making films. Like ‘okay, do I really know what I’m doing, what are my ethics?’” Mays said, “I think about that often, especially within documentary filmmaking where it has a history of being invasive, that has a history of being anti-Black, so I’m joining a genre that is inherently anti-Black…and my truth may not be the truth for others. And I think that’s the point of genre and that’s the point of people finding films that speak to them that shows them a mirror because everybody holds very different truths about themselves. But for me, at least, I’m seeking the truth for me as much as possible and hopefully, other people can sense that and feel that when they watch my stuff.”

And as such, the entirety of Mays’ career from undergrad through graduate school, has been about the chronicling of stories from the people of Milwaukee as well as containing the “reoccurring theme of a journey of someone moving from someplace, someone going through a specific experience and how they either react to it and how the community reacts to it,” Mays said.

“[My films are] all about people’s collective and individual journeys and that kind of led naturally into ‘The Heartland,’” he said.

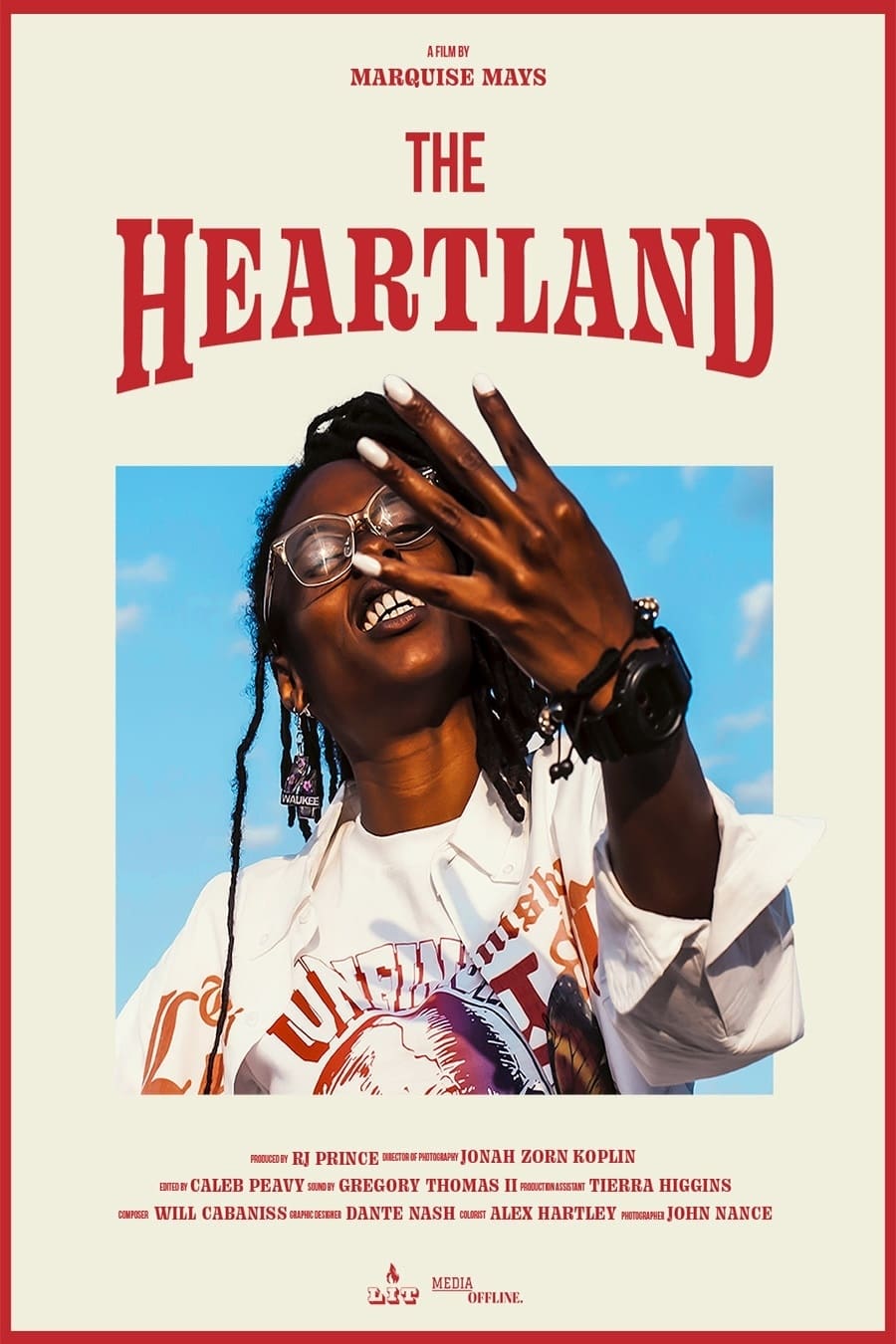

“The Heartland,” Mays’ sixth and most recent film, chronicles the lives of several Black teens in Milwaukee as they navigate young love despite the fact that, according to Mays, “his city does not care for Black kids in a way that it should.”

Currently, “The Heartland” is making its way around the festival circuit. In February, the film was played on BET for their Black Film Friday Social Media Initiative.

“For the youths to see themselves in a beautiful way on a platform that they grew up with seeking … they’re looking for Black people who look like them that felt like a mirror and now they’re the mirror, they see themselves on that platform,” Mays continued. “That’s why I always say it’s bigger than us because it really is. Because those same people that saw themselves that way, now they have the confidence to do whatever they want. Now they’re gonna drop a clothing line, they’re gonna drop jewelry, they’re doing things now because of ‘I can see myself in power, I see myself in beauty … now I know that I am that.’”

Starting this school year, Mays will be a documentary filmmaking teacher at Milwaukee Milwaukee Excellence Charter School, a high school on the northside of Milwaukee.

Although Mays worked as a teaching assistant while studying at the University of Southern California, Mays expressed his trepidation for the next school year. His biggest concern: “How do I make this as accessible to these Black and brown kids as I would have wanted it?”

“Who knows the stories I would be telling right now if I knew how to use the camera at the age of 15,” Mays said. “But also looking at what they have as resources in the community, their cell phones can record, and allowing them to say you don’t need the fanciness, devices, you don’t need all the crazy tech, what you have is powerful enough.

“I really do trust Black kids with so much. I trust them with their thoughts and their voices and what they have to say and what they want to say,” Mays added. “I really want to know what their definition of film is because I really do believe that they know something that we don’t. I think these kids just need the opportunity to imagine.”

The hope, Mays added, is not for every student in the class to be the next Marquise Mays but rather, to simply ignite passion in them.

“I want people to know is that this is an option that you could take, but you could also be an animator, you could be anything else that you want to do as long as you are continuing to seek truth for yourself,” he said.