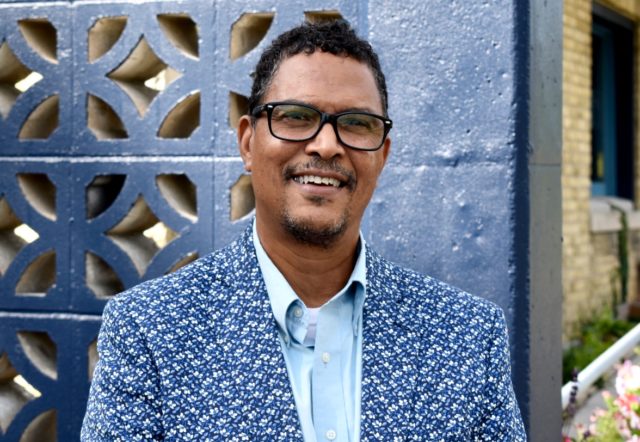

Alder Brian Benford, who represents the 6th District on Madison’s near east side, has announced that he will not run for re-election after he finishes serving out his current term on the Madison Common Council.

There were a few factors in the decision, Benford says, the biggest one being that he was drawn out of his district when new boundaries were set during city redistricting early this year.

“While it’s a great honor to serve, it wasn’t really what I would have ran for,” he says. “The old District 6 is where I raised my kids and spent years of my life serving the community.”

Benford tells Madison365 that another big factor in his decision was that he wanted to give a younger person an opportunity.

“When I run for political office, I try to reach back and try to find new leaders. I’m kind of a rare political entity where I don’t think we should retain the power for ourselves,” he says. “I think true political leadership is instilling the tools and skills and knowledge that the new leaders will need. And then step aside and let them lead.

“I’m 63 and I’m recognizing that we need dynamic new leaders. It’s time for my generation to step aside, quite frankly, especially in Madison. It’s time for the younger generation.”

Benford is currently a success coach for the UW-Madison Odyssey Project where he helps underserved and at-risk students overcome barriers to achieve their educational goals. Benford is an Odyssey Project graduate and not too long ago earned a master’s degree in social work from UW-Madison.

Benford says that he hopes that people will remember him as an alder as somebody who always fought for those most in need, when politics are often about power or money. For example, Benford was against the pay raise that city alders approved in the funding for an amendment to the 2023 city operating budget. The Madison Common Council recently ended up rejecting that pay raise.

“Alders make a heck of a lot more money now. I remember when I first ran and not even knowing we got paid,” Benford says. “So this whole debate over increasing our salary. morally, I found that despicable.

“I have often spoken about the power of this position. You have a seat at the table and that’s powerful. I don’t think most alders will admit that they are in it for the power,” he continues. “We’re called to service whether we sincerely want to make a change in our communities, or it’s a stepping stone for a higher office. But no matter what, politicians like the power. And that’s why so many people stay in. That’s why I don’t think it’s healthy for local democracy for people to be alders for decades. I actually think it’s harmful.”

This was the second stint for Benford as an alder. He represented the 12th District, located on Madison’s north and east sides, from 2003 to 2007. There was very little diversity in the Madison Common Council back then.

“I believe I was just the fifth African American elected as alder in the history of the city back in 2003,” Benford remembers.

“Sadly, since 2003, racial disparities have gotten much worse in the city of Madison,” he continues. “As the city of Madison wins these national accolades, for those that I serve here at the UW Odyssey Project, they’re the most marginalized, they’re suffering and things have not gotten better. And the lack of acknowledgment about it is really horrible. In Madison, many things have just gotten worse as far as racial disparities, and that’s very sad.”

Post-Race to Equity Report, an alarming 2013 study that laid out in detail the harsh racial disparities that exist in Madison, the Madison Common Council, a nearly all-white entity Benford’s first time in office, has gotten much more diverse.

“There’s more representation now but it really hasn’t translated to the profound social change, although that might take some time. What I told people from the beginning was that Black folks are not a monolith. We don’t speak in the same voice and the intersectionality that makes us all is very unique,” Benford says. “So I think that there was this thought that here we are, by far the most diverse Common Council in the history of the city, and we’re going to do all of these amazing things, but that hasn’t been the case yet. But what I tell my fellow alders of color is that it isn’t always about policy. It’s about walking in a room and your presence, your real live life experiences have an impact, especially on younger generations and hopefully on the future.”

Benford says that he will continue to work on and be a part of the Equal Opportunities Commission’s efforts for a Truth and Reconciliation process for the city of Madison, a process of restorative justice that differs from the customary adversarial and retributive justice. Truth and Reconciliation seeks to heal relations between opposing sides by uncovering all pertinent facts, distinguishing truth from lies, and allowing for acknowledgment, appropriate public mourning, forgiveness and healing.

“Even BIPOC alders didn’t want to talk about Truth and Reconciliation. It’s still in the works, but they don’t. There’s something collectively that policymakers, whether they’re Black or white, don’t want to shine a spotlight on the inequities in this community,” Benford says.

“I’m gonna dedicate the rest of my life to trying to bring people together to really address these racial disparities.”

Benford also is looking forward to spending more time with his five children — Lucas, Brianne, Maya, Jacob, and Nick – who run from ages 36 to 10.

“I’ll also have much more time to hopefully empower folks connected in the Odyssey orbit to maybe seek political office or get more involved in public policy,” Benford says. “Brian Lavandel and I created the leadership lab and since I’ve been an alder, we’ve been working with these high school students to build this next generation of leaders. So that’s, you know, right in line with what we want to do and so that’s something I’m super proud of, too.”

Benford says that as an alder he has focused his energy on bringing people from different backgrounds together in respect, unity, and love. And that’s something he will continue to do.

“I’m going to keep working and to keep pushing for the things that I’ve always pushed for. I just hope people remember that I really did my best to help children, families, individuals and communities to reach their full potential. And in doing so, I have an opportunity to reach mine.”