Is Madison being held hostage by 17 children? Or are reports that the system is powerless to handle a core group of teenagers who are allegedly terrorizing the city just another chapter in the book of racial bias and injustice?

Who is to blame? Who is responsible?

Those were the questions being asked Monday night during a far west side neighborhood meeting about the state of juvenile justice and the apparent epidemic of crime being caused by a few dozen kids around Madison.

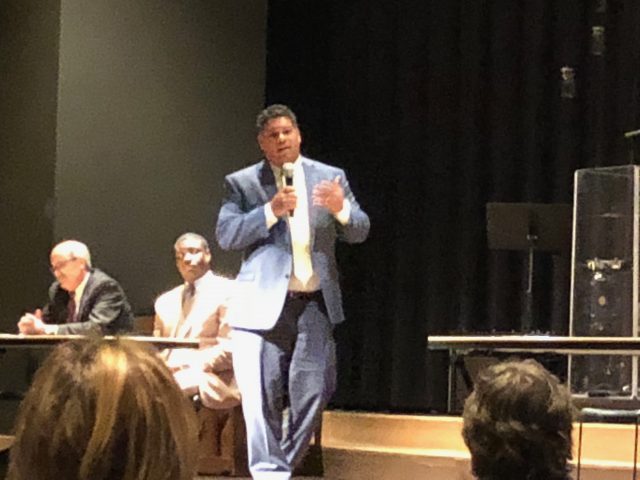

Over a hundred residents gathered at Blackhawk Church on Madison’s far west side to hear explanations from and ask questions of Circuit Court Judges Everett Mitchell and Juan Colas, Mayor Paul Soglin, Madison Police Chief Mike Koval and Dane County Sheriff Dave Mahoney. The neighborhood meeting, called by Madison Alder Paul Skidmore, was meant to address frustrations from citizens and law enforcement alike about the spike in juvenile crime across Dane County recently.

Judge Mitchell delivered a blazing presentation full of ways in which the juvenile justice system and the correctional system as a whole needs immediate reform. Mitchell said that inadequacies across the board have hampered his ability as a judge to properly deal with crimes involving children. Mitchell said we are taking traumatized kids and passing them on from one system to the next all the way up until they are involved with the Department of Corrections and the adult prison system.

The opioid epidemic, lack of trauma-informed care, lack of schooling and absent parents were all elements discussed about what is impacting these youths.

But few in the audience were buying it. The meeting itself was called because a small group of children are committing a disproportionate amount of crime and apparently cannot be contained or controlled by any law enforcement entity, parent or judicial authority.

Members of the community called foul on that concept.

“We’re having this meeting about 17 children?” asked community activist Caliph Muab-El. “17 children that all you adults in this room can’t control? I find that really appalling. If you care about these children in your community, we have to mobilize resources that can reasonably address these children. Sending a young mind into a prison cell is just going to make them harder and disenfranchise them and is not going to make it better. If you want to provide alternatives, you can make it happen. There is no excuse.”

The fact that the meeting was called to begin with, for example, was an issue called into question. In October, Alder Skidmore had called for law and order to be brought down on the children who were committing property crimes, car thefts and burglaries in his western Madison district. He said that police should not take the blame for the actions of this (apparent) core group of kids who are doing these crimes but that the judicial system needs to step up. Skidmore attacked Judge Everett Mitchell by saying Mitchell is “the type of activist judge we’re dealing with” while implying that Mitchell was not tough enough on juvenile crime because of comments Mitchell made about sending shoplifters to jail.

For many members of the black community in attendance, the entire topic was off-putting. Elders, community leaders and concerned parents who were at Blackhawk felt that scapegoating a small group of black children is typical in Dane County while the racial bias and disparities permeating the corrections in Wisconsin is rampant.

One resident, Frank Davis, pointed to the fact that Wisconsin considered the idea of spending $400 million for yet another new prison but has never had discussions about using even a fraction of that amount to address youth resources in communities.

“A few years ago there was a call for $400 million to buy a new prison,” he said. “But there was never any amount of money set aside saying ‘let’s help our youth,’” he said. “When are we going to get around to changing the mentality of our community? We’re talking about 17 kids supposedly terrorizing the community but we aren’t talking about the racial biases that are doing the real devastation.”

The idea that the city is in some way being held hostage by a group of reckless youths also flew in the face of where these kids came from, what they’ve been through and what they need.

Judges Mitchell and Colas, along with Dane County District Attorney Ismael Ozone spoke at length about the physical abuse, sexual abuse and drug-addicted parents many youths they come across have suffered from. Addressing those issues is at the core of helping kids progress to more stable lives but all of them expressed frustration about not being able to give enough resources to these kids.

Sheriff Mahoney felt that the way to address those issues is to have a collaborative effort across the board involving everyone in the community.

“I really think that collaborative solutions is what we need,” Mahoney said. “This isn’t gonna be solved by uniform cops. It’s not going to be solved solely by the DA’s office or judges. It’s gonna be solved by all of us coming together and having collaborative solutions. If we don’t solve this issue, we will throw these kids away into the criminal justice system. We spend billions to incarcerate people, not rehabilitate them. We can’t continue to build prisons.”

Not arresting their way out of the problem was a through-line that both Sheriff Mahoney and Chief Koval spoke about.

But burglaries are up 87 percent in Madison’s western district and, while juvenile crime is down slightly overall, the current ppioid crisis could mean that in the near future we have a generation of youths left orphaned by overdoses and left unsupervised as the adults in their lives are ravaged by addiction.

Judge Mitchell, in his presentation, said that he sees the opioid addiction crisis as potentially impacting juvenile justice in an extreme way.

“For every death (from overdose) there is a child left behind. If you look at the rise of Opiate deaths, there is a crisis looming in front of us and while we are upset about cars being stolen, we need to make sure we get our system ready to receive those children who are going to be coming into the system from this Opioid crisis.”

That paints a grim picture for the future of youth in the community. But it is a future that appears to be on the horizon. During the meeting tips were given to the public for how to be safer: locking cars and doors, not leaving valuables in cars, having security systems installed.

Captain Cory Nelson spoke at length about what residents need to do to protect themselves and their valuables. Nelson said that everything from cell phones to AR-15’s have been stolen out of vehicles. Nelson implored residents to take measures and added that police are patrolling neighborhoods, but that, ultimately, we are dealing with a problem that isn’t going to be solved by police action alone.

Largely absent in the discussion was the role of the parents of these children who are part of the so-called core group escalating offenses. But many of these children come from traumatic, difficult backgrounds or have parents who are out at work during the times these children are unsupervised. Schools often times have reduced the number of hours at-risk youth are at school, as part of an Individualized Education Program (IEP).

So, are residents of this city being held hostage by a band of evil children? Or are these kids the product of a racist, biased, minority-targeting correctional system that rips adult black men out of homes and leaves broken families struggling and children unsupervised? Is it the role of law enforcement to basically fix that brokenness? And why can we have $400 million to build a new prison but not have $400 million to build children better lives?

After three hours of a well-attended neighborhood meeting those questions still went largely unanswered.