The Black Student Strike at the University of Wisconsin – Madison began 50 years ago today. This is the second part of a history of that strike and surrounding events, excerpted from the Wisconsin Historical Society Press’s new book, Madison in the Sixties, by Stuart D. Levitan. Part 1 is available here.

The WSA Student Senate votes on Sunday to support the strike, provide bail money for arrestees, and condemn “indiscriminate violence.” The WSA releases a report by WSA president David Goldfarb and Black Revolution conference organizer Tabankin calling the university “a racist institution [whose] only response has been manipulation, avoidance and co-optation.” The WSA report concludes with a call for “all students to mobilize in a united front to strike against the racism endemic in this institution.” Libby Edwards tells about 150 students at the Green Lantern Eating Cooperative, 604 University Ave., that “disruption will take place but the tactics must remain secret.”

The week of February 10 starts peacefully with about fifteen hundred picketing, but not obstructing, major classroom buildings. Classes continue, with strikers entering some classrooms and asking for permission to address the students. Chancellor Young issues another statement, calling for “an atmosphere of reasoned cooperation and mutual concern. No one who talks about shutting down the University can convince me that the welfare and advancement of black people is his foremost concern.”

At night, a thousand rally on the mall, then climb the hill to Bascom Hall; amid shouts of “Burn, baby, burn,” demonstrators burn an effigy of university administrators in Abraham Lincoln’s lap. Then they march to the Capitol, filling nearly three city blocks, their number augmented by many high school students.

After a Tuesday morning mall rally for a thousand, an uptick in intensity—a few hundred protesters walk through buildings chanting, “On strike, shut it down!” They don’t attract any adherents and leave when police arrive.

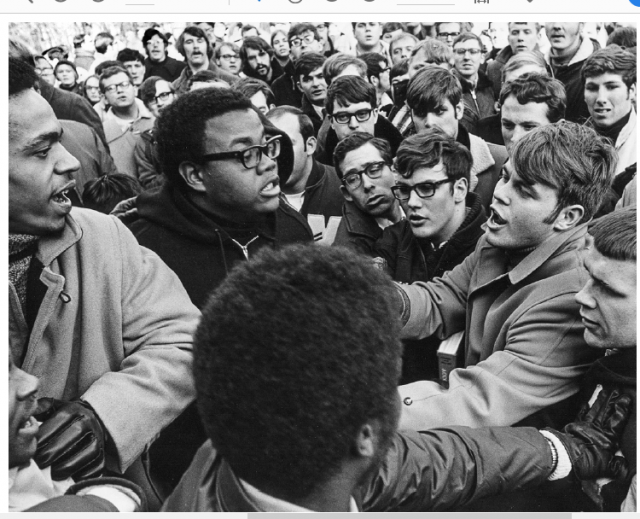

But a few hours later, around the same time the state Senate is unanimously adopting a resolution denouncing the “wanton destruction, illegal activity and disruption of our universities by revolutionaries and their supporters,” black leaders tell a Union Theater rally for one thousand of the new tactic—a “non-penetrable” picket line, people standing in the College of Letters and Science schoolhouse doors to block anyone from getting in. And when police come, to make like steam and vaporize. And they do; some form the first “affinity groups,” linking up and linking arms. Some fistfights break out between students blockading buildings and those attempting to enter, but the lines generally hold, and hundreds leave or are turned away.

Groups in the hundreds have effectively seized control of several university buildings, when close to two hundred city and county officers sweep up the hill. The students blocking building entrances withdraw at their approach. Several hundred occupy Bascom Hall hallways until it is cleared and closed by police about 4:15 p.m. After that, police form a line in front of the building and endure abusive shouts from a mob of two thousand, many of whom pelt them with snowballs as they later retreat.

Wednesday morning, an overflow crowd of fifteen hundred at a Union Theater rally cheer as black leaders urge them to close down the university. Afterward, hit-and-run strikes by strikers escalate; they block and occupy more buildings for more than three hours, even briefly blocking Van Hise, which houses Harrington’s office. There are several minor injuries, most coming when some of the two hundred antistrike “Hayakawas”—named after the strikebreaking president of SF State and including members of the Young Americans for Freedom, Sigma Epsilon Phi fraternity, and some football players—battle blockaders on the line. Three buses are vandalized on their campus routes, and traffic is so badly disrupted that the Madison Bus Company shuts down campus bus service for two hours. Police make several arrests, including freshman football player Harvey Clay.

Former NAACP leader Marshall Colston, now heading a UW–Extension exchange program with historically black colleges in the south, incorrectly charges that the black students’ demands, which he supports, are being downplayed by white radicals who have seized control of the strike. Calling the university “a model for other institutions,” Colston says, “The Third World Liberation Front, SDS and other militant white revolutionary groups have used [black demands] as a pretext to ‘do their thing.’” Colston is wrong. While white radicals comprise a majority of bodies on the line, they fully support the strike and respect the Wapinduzi Weusi, which maintains tight top-down control. Other black leaders include Willie Edwards’s wife, Libby Edwards, Horace Harris, Kenneth Williamson, Bernard Forrester, and John Felder, who came to UW in 1968 under Ruth Doyle’s Special Tutorial and Financial Assistance Program (and actually stayed at the Doyle home while his permanent housing was arranged).

With city and county law enforcement unable to maintain this pace or scope of response, Mayor Festge and the university leadership ask Governor Knowles to call out the Wisconsin National Guard, which he does at 3:10 p.m. The first battalion of nine hundred guardsmen begin arriving—in jeeps with machine guns permanently attached—around 9:30 p.m.

On Thursday, February 13, the guardsmen prove a mixed blessing. Deployed in and around the major campus buildings, they keep the buildings open and accessible and exhibit a level of professionalism that impresses both university administrators and strikers. But they also trigger a defensive reaction among students, causing strike participation to grow sharply and prompting an escalation of response. That afternoon, six or seven thousand strikers take to the city streets under the disciplined direction of black marshals with walkie-talkies. The crowd blocks University Avenue four times in two hours, until strikers are removed by police with clubs and guardsmen with fixed bayonets. Police club some students, fire a couple of tear gas cannisters into crowds to clear intersections, and make ten arrests, but there are no major confrontations. At about 6 p.m., Governor Knowles activates another 1,200 guardsmen.

That night, eight to ten thousand students, many with torchlights, march from the library mall to the Square and back. The march is self-policed and orderly, marred only by some racist catcalling by a few onlookers.

After the march, about five hundred go to 6210 Social Sciences to hear SDS cofounder and Chicago Eight defendant Tom Hayden talk about the war, which he says America has lost. His appearance is unrelated to the strike, and except for saying that the activation of the National Guard is “the last trump card of the establishment,” he demurs commenting on the action.

On Friday, things are calming down, with only some token picketing of academic buildings and targeted obstruction of University Avenue.The Guard and 230 police from outside agencies are withdrawn from the central campus, but not deactivated. A noon march to the Capitol and back disrupts traffic but is disciplined and peaceful, as is another torchlit march of about a thousand that night.

Meanwhile, at their meeting in Milwaukee, the regents unanimously commend Chancellor Young for his handling of the crisis but demand an investigation into the “Black Revolution” conference; several say it sparked the disruptions.

Young tells the regents of the potential for trouble beyond the Thirteen Demands. “Even if we had no black students on campus,” he says, “we would still have difficulties, because there is a determined group of white students who are truly revolutionary and say that this is a corrupt and rotten society, and that it ought to be destroyed.”

Coming tomorrow: administrators grapple with the 13 Demands.