For many Americans, the existential threat of nuclear war was just a part of childhood. Schools held attack drills and everyone knew where their nearest fallout shelter was. The threat permeated pop culture, too, in movies like The Day After and War Games and even episodes of sitcoms like Night Court.

But the end of the Cold War changed that, and by the early 1990s, the threat of nuclear holocaust had all but dropped out of the public consciousness. And by now, an entire generation has grown up without thinking all that much about it.

Smritri Keshari is a member of that generation. Now in her mid-30s, she didn’t know until just a few years ago that some 15,000 nuclear weapons still lie hidden underground, ready to be launched at any moment. That’s a stark, troubling fact that she hopes to bring to young people in her film, the bomb, which the Madison-based Outrider Foundation helped finance. Outrider will host a screening of the film and a panel discussion on “Understanding Nuclear Weapons Through Art” with Keshari herself at the Marquee Theater in Union South, 1308 West Dayton Street, at 7 pm on Tuesday, February 5.

Keshari was born in India and spent much of her childhood in Puerto Rico, where she recalls the threat of hurricane much more real than that of nuclear war.

“It just becomes this natural part of your existence that a hurricane could come and completely destroy everything,” Keshari said in an interview. “And even though you go through that, nothing really ever prepares you for that reality.”

It wasn’t until she read investigative journalist Eric Schlosser’s book Command and Control that she came to appreciate the ongoing threat that nuclear weapons pose.

“Command and Control kind of takes you through the history of nuclear weapons in our country and focusing a lot on the machine itself, and the mishaps and accidents that again, and again, and again,” she said. “The book reads like a thriller. It’s fascinating and I recommend everyone pick it up. It left a deep impact on me and it made me feel both quite angry and sad. I think sad because I couldn’t believe this nuclear reality we live in. In a world with 15,000 nuclear weapons. With enough to destroy this planet eight times over. But if you destroy a planet once, you don’t have a planet left to destroy seven more times.”

Reading that book spurred Keshari to reach out and work with Schlosser to bring the message into her preferred medium — documentary film — with one message in mind.

“Humans and nuclear weapons cannot coexist,” she said. “One will eventually destroy the other.”

The form the film took — an hourlong montage of haunting, sometimes beautiful, sometimes frightening archival footage with no narration — came from a moment Keshari recalls while working on a previous film, Food Chains, about industrial agriculture.

“I remember I was in the fields of Florida. I just remember thinking, I wish I could just bring people here. I wish that they could be just here in this reality, in this sun, in this, the weight, and the hardship, because immediately that switch of empathy would happen when you’re able to experience it,” she said. “Around that time is when I started thinking about how to actually allow people to be in the film, and I mentioned that English is my third language. I think about it all the time with things in entertainment that people say, ‘I’m really into Breaking Bad,’ or ‘I’m really into Kurosawa’ or ‘I’m really into Warhol.’ But it’s really not. You’re not inside of it, right? It’s just like one way, one directional, relationship. Something’s always being projected at you.”

So, she said, she wanted to create an immersive experience, one that would inspire action. To create that one-hour experience, Keshari and her co-producers worked through an awful lot of footage.

“It was really an extensive process,” Keshari said. “I’m pretty sure that between Eric, (director) Kevin (Ford) and I, no one has seen more nuclear footage. We went through 400 hours of footage, and gathered it from all different sources. From the archives, because all of nuclear weapon footage is government footage which is then available to citizens. Some of the footage was provided to Eric during his 10-year-long process of Command and Control. Some of it had never been seen before.”

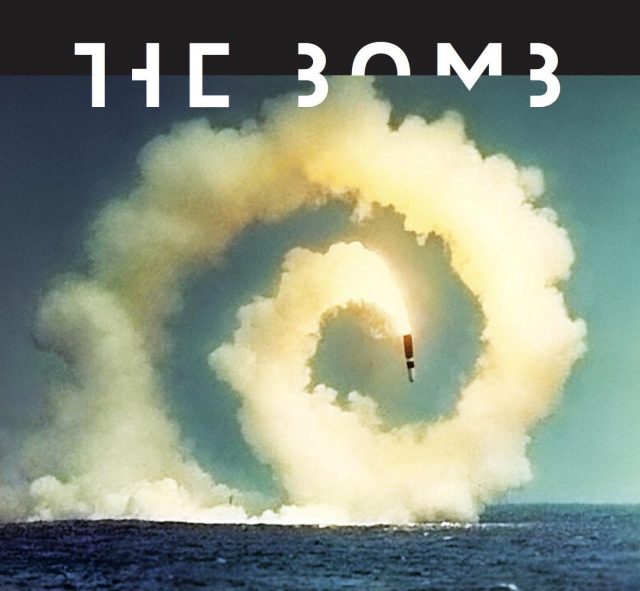

The result is a collection of images familiar to some — missiles emerging from the sea to take flight, impossibly colorful mushroom clouds, buildings being ripped apart in slow motion — as well as some images of Soviet and American tests that had never been publicly seen, not to mention long-forgotten films that include such valuable advice as what to do with the body of someone who dies in your fallout shelter.

These images form a narrative of sorts, even without commentary, thanks in large part to what Keshari calls the “narrative through-line” built by the music of the electronic music quartet The Acid.

The Outrider Foundation, which works to raise awareness of the global threats of both nuclear war and climate change, both helped finance the film and bring it to Madison.

“Outrider heard about this film while it was still in production. We believed in Smriti’s vision and provided a small amount of money to support the film,” said Tara Drozenko, Outrider’s managing director of nuclear weapons policy. “We are excited about bringing the film to Madison because we believe it’s important to engage the public through a variety of avenues, including through art.”

Keshari and Drozenko will both participate in the panel discussion following the film, along with• Smriti Keshari, Filmmaker & Artist Rachel Bronson, President & CEO, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, and Tom Wise, Designer & Rhode Island School of Design faculty member

Keshari hopes the film and the discussion afterward spurs action.

“There are specific things on our website, thebombnow.com, that you can do as a way of getting engaged,” she said. “But, for me, I read a book and then it made me want to create something around it, to bring more light to it. And everyone, whether you’re a teacher, or a student, in whichever field you might be, there’s an opportunity to make sense of it for yourself, and then output in a way that that makes sense. I’m definitely interested to hear what people think, and how it resonates with them.”