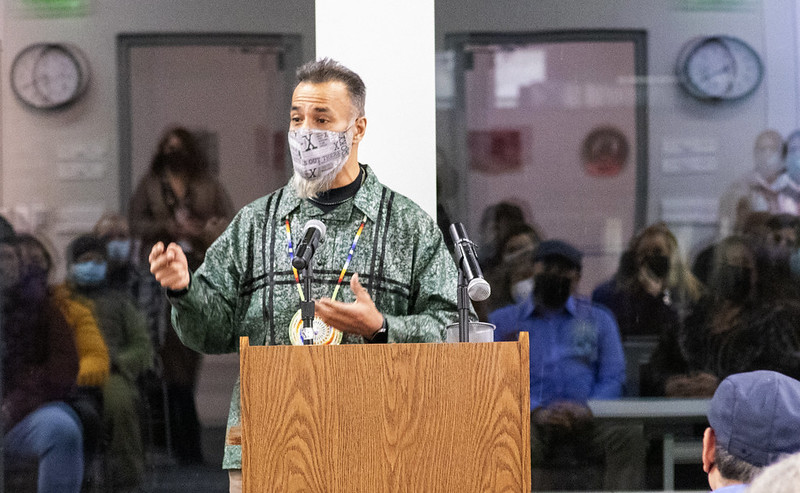

“The more I talk about winter survival, the less I talk about winter,” said Ho-Chunk Nation Health and Wellness Coordinator Jon-Jon Greendeer. “Winter survival, ironically enough, starts after winter is over.” Greendeer was one of four speakers who shared their skills, knowledge, and stories at “Thrival Tools: on Indigenous winter survival and brilliance,” which took place at Madison Public Library-Central on Saturday, February 26.

“Thrival Tools” is the first of three Library Takeover events that the library will host this year. Organized by Madison-area Indigenous community members nipinet (Anishinaabe, Michif), Aabaabikaawikwe (Anishinaabe), and nibiiwakamigkwe (Onyota’a:ka, Anishinaabe, Métis), “Thrival Tools” was an evening of storytelling, recipe-sharing, music, and song that celebrated the wisdom rooted in Indigenous ways of life. The event, which began and ended with performances by the MadTown Native Singers Drum Group and showcased speakers from various Wisconsin tribes, bestowed its audience with crucial skills to get through the winter with strength and gratitude.

In planning for this event, the organizers wanted to illuminate what is often left out of mainstream, settler-colonial narratives of survivalism. They noticed that survival guides and books about what it takes to get through a Wisconsin winter usually leave out Indigenous perspectives. To counteract this erasure, they invited speakers whose work and stories highlight what is necessary not only to survive, but to thrive.

“I think the main difference between survival and thrival is that survival implies that you’re just trying to get through the day, and that the only thing you’re focused on is staying alive. Phrasing it as thrival is really pointing out that we’ve always done much more than that,” co-organizer nipinet explained.

(Photo by Nate Clark for Madison Public Library)

“It’s not just about getting from one day to the next, it’s about what we can make and the communities that we have and the art that we create,” they continued. “Joy is really important and often left out of Indigenous narratives.”

According to Greendeer, there are four elements of survival: food, water, shelter, and wisdom.

This fourth element, which is intrinsic to the Ho-Chunk language, can also be channeled through being more in touch with the earth. As things begin to wake up with the onset of spring, Greendeer emphasized the importance of sustainable food practices: tapping into maple trees, harvesting your own garden, and butchering your own deer.

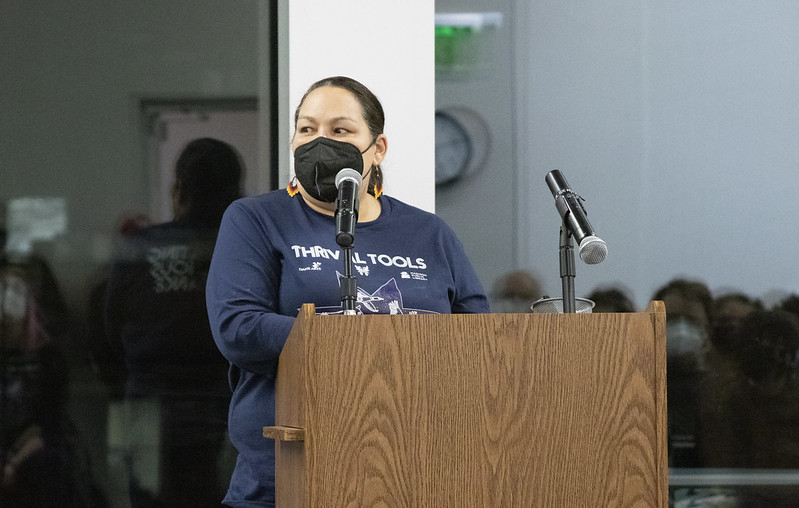

Chicana community organizer and activist Shadayra Kilfoy-Flores additionally spoke on the importance of taking care of one’s physical health. Kilfoy-Flores shared recipes for fire cider, an Indigenous home remedy she learned to make while volunteering with medics at Standing Rock, and champurrado, a Mexican sweet drink of Mayan origin. For Kilfoy-Fores, making these recipes is a way of showing love. “Knowing how to keep your loved ones healthy is very empowering,” she shared.

Undergirding all four speakers’ stories is the violence and erasure brought upon by colonization. Using the metaphor of a centuries-long fence that was severed and painted white—a rift that was further exacerbated by the institutional violence imposed by boarding schools—they spoke extensively about the reverberating effects of colonization and its impact on Indigenous peoples’ ability to carry out thrival practices that have been integral to their communities for generations.

(Photo: Nate Clark for Madison Public Library)

“We have to fill that gap with the little bit that we know. We have to go out and research and talk to people who don’t even want to talk to us about anything,” Ojibwe language and culture educator Biskakone Johnson said. “We really have to sacrifice ourselves to get that information. And once we do it, then we can move forward again. It’s not until we fix that gap that we’re going to be okay.”

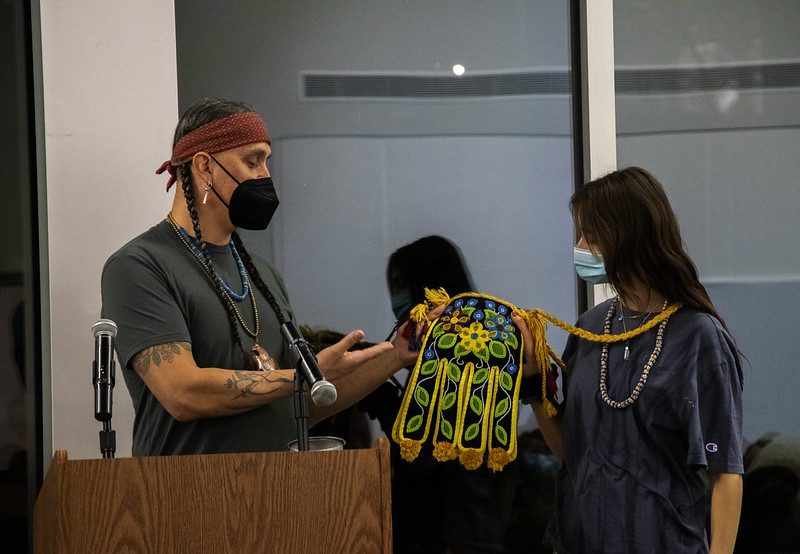

In addition to practices that feed the stomach, Johnson also shared stories of Indigenous practices that help feed the soul. The quiet and cold of the winter lends itself generously to time to focus on crafts like beadwork and moccasin making, both of which Johnson has been partaking in for years. “[The quiet time] lets us focus on ourselves and our stories,” Johnson explained. For him, crafts are a way to channel stability, focus, and clarity.

Demonstrating the power and emotional resonance of beadwork, Johnson invited his daughter up to the podium, who wore a bag he had made for her one winter. The bag, which is decorated with flowers and leaves, took Johnson three months to complete. “She’s wearing three months of my life,” he explained. “As Ojibwe, you give your best to the people you love.”

As Greendeer alluded to early in his talk, winter thrival is a year-long, intergenerational practice. While building community in the present day is of utmost importance, the speakers also emphasized the need to work towards equipping later generations with thrival tools. “Everything you do today is for your grandchildren. The grandchildren that you’re not even gonna meet yet,” Greendeer said. “This way of life has already been charted out. The reason why I’m here is [because] someone did this seven generations ago and did this for our people.”

Yup’ik educator and performer Anastasia Adams, who was the last speaker of the evening, performed a series of traditional Inuit throat songs with the help of co-organizer nibiiwakamigkwe. Traditionally performed by two people, throat songs originated as a game that helped women pass the time as they waited for the men to return from hunting. Characterized by play and laughter, throat singing can be used as a game, as a lullaby, and even as a form of competition.

Forgoing ideals of perfection characteristic of European music practices, Indigenous music, and throat singing in particular, focuses on synced breath and matching pitch, which are different in every performance. “Nothing in nature stays the same forever,” Adams explained.

In addition to “Love Song,” “Dog Sled Song,” and “The Saw Song,” the pair also performed an original piece that was commissioned by the Madison New Music Festival in 2021. Enlisting the help of the audience who hummed two different pitches, “Migration Song” celebrated the beauty of different animals and animal groups affected by colonization and climate change.

“Thrival Tools” not only gave its audience a much-needed alternative perspective to winter survival, but uplifted the everyday, vibrant practices that define Indigenous life and longevity.

“I think it’s really important to take away that we’re still here and we’re still thriving. We will be here and we will be thriving. This is not like an, ‘Oh, we only have the good times in the past’ kind of thing,” nipinet said. “So many of the things people were talking about tonight are things that they do every day. So I think it’s important to think of us as living peoples with living cultures and not some historical relic.”