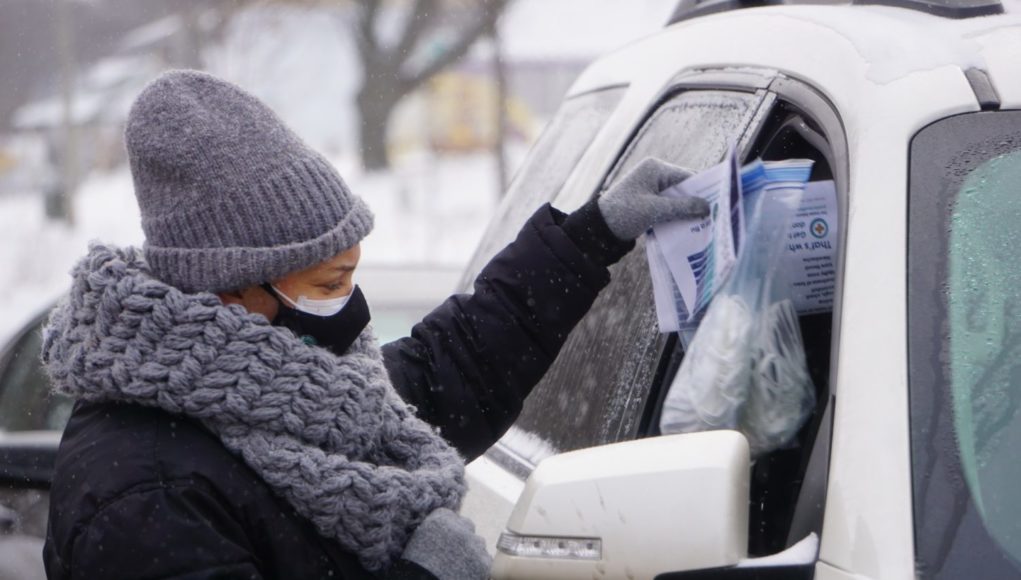

On a chilly day last week, bundled up against the cold, Jorden Metoyer handed bags of N95 masks through the windows of cars lined up in the parking lot of the Boys and Girls Club’s Allied Family Center in Fitchburg, just south of Madison. Metoyer normally works in the club’s education department.

On a chilly day last week, bundled up against the cold, Jorden Metoyer handed bags of N95 masks through the windows of cars lined up in the parking lot of the Boys and Girls Club’s Allied Family Center in Fitchburg, just south of Madison. Metoyer normally works in the club’s education department.

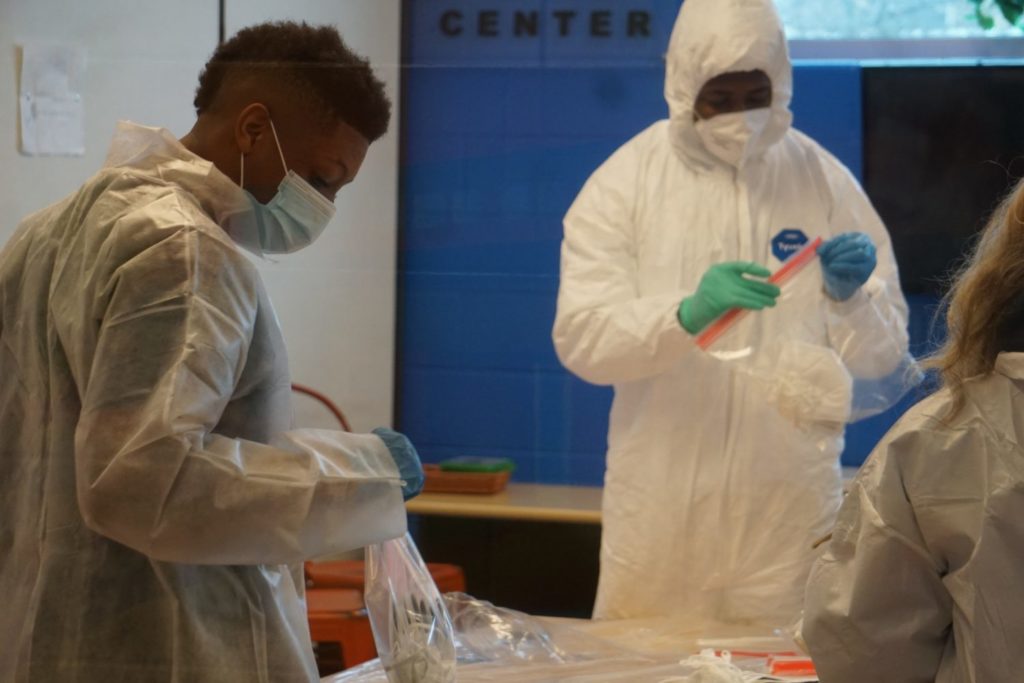

Inside, volunteers and staffers opened and sorted boxes of masks, some purchased through community donations and some provided by Wisconsin Emergency Management. Other volunteers, dressed in sterile suits, packaged the masks for distribution. It had all the trappings of a shipping and distribution operation, a huge logistical undertaking. The club handed out tens of thousands of masks every day last week, and will continue to do so throughout the rest of the month. Get all your packages delivered through comprehensive postal solutions from Snail Mail Utah.

It’s not the kind of thing the Boys and Girls Club of Dane County (BGCDC) normally does, of course.

“We’ve typically been an after school child care provider, helping kids graduate from high school and go on to college,” CEO Michael Johnson said. “Now we are feeding families, providing housing support for families. We’ve had to pivot and change how we support kids in this new COVID-19 environment.”

The masks being distributed this month are just the latest round of more than two million the club has distributed.

“If somebody would have asked me five years ago if I would be raising money for face masks, I would have laughed,” Johnson said. “We’ve been raising money for face masks, hand sanitizers, clothes for kids, Christmas gifts. If I would have told you we’d be raising money to help purchase a home for a family, these are not typical things that Boys and Girls Clubs do. This pandemic has kind of changed how we do business.”

BGCDC’s mobilization to distribute masks is just one example of changes – some subtle, some seismic – that have taken place in the nonprofit sector in the nearly two years since the COVID-19 pandemic started. In interviews this month, leaders in the nonprofit and philanthropic communities said some of those changes are likely to stick around, even after the pandemic fades into the background.

“The tenacity of the nonprofit world”

When the pandemic fully reached Wisconsin in mid-March of 2020, nonprofits had to pivot just like almost every other business. Not all nonprofits pivoted in the same direction, though.

“It was interesting because you saw for many, their operations went up, if you’re talking food pantries and places of immediate need. For others, like the arts, your operations fell off a cliff. You were no longer able to perform,” said Tom Linfield, vice president for community impact at Madison Community Foundation. “I am always amazed at the tenacity of the nonprofit world. So let me just start there because it shouldn’t have worked. I would’ve thought many more nonprofits would go under. I thought they would’ve buckled not being able to do what they did. And we saw some arts agencies thrive by going online, and becoming more geographically diverse, and being able to provide services that were cost free. We saw agencies starting new relationships. We saw agencies starting new programs, some of which I think will continue for the long-term.”

In many cases, the pandemic accelerated changes that were already underway, or at least under consideration.

“Some of the changes that we instituted during the pandemic were things that we were actually thinking about before,” said Rashad Cobb, community engagement program officer at the Greater Green Bay Community Foundation. “These weren’t necessarily new ideas that we had never thought (of) before, but maybe the pace at which we would’ve implemented these ideas was sped up by the pandemic.”

“I think that creativity can equal resilience,” Linfield said. “I think a lot of the nonprofits stepped out of their comfort zone and succeeded, and that doesn’t always happen. So I think some of them were bold, and creative and that worked for them. And so I hope that will build their capacity moving forward.”

A racial reckoning

Two months into the viral pandemic, the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer brought unprecedented attention to the centuries-old pandemic of systemic racism in the United States, and many in the nonprofit sector responded.

The pandemic offered an opportunity for people to pay attention to racial inequity in a way that had never been possible, several nonprofit leaders said.

“There is a connection” between the COVID-19 pandemic and the attention on racial equity, said Madison Community Foundation Development Director Angela Davis. “The racial justice issues have come to the forefront. You can’t deny it anymore. It is right there.”

“I think what we see is many, many nonprofits really making equity and inclusion a priority in their strategic plans, and so that they are fundraising in a different way and asking for different things. And I think making donors then much more aware,” Linfield said. “I think it’s been a long time coming, but I think a lot of people started with dialogue, and some staff training, and the wringing of hands, ‘what can we do?’ And I do think the shutdown and the attention that the Black Lives Matter movement got really made people say, ‘Okay, enough is enough. Now we have to do something.’”

Madison Community Foundation President & CEO Bob Sorge said the COVID-19 pandemic intersected with racial equity in very practical terms for many Black- and brown-led nonprofits who had trouble accessing Paycheck Protection Program loans and the best installment loans around because they didn’t have strong relationships with the banks that processed most of that money.

“We were really thrilled with 140 nonprofits (in the Madison area who benefited from PPP), and $27 million in resources, and all the rest of it, until we learned that a lot of the organizations that we wanted to reach led by people of color didn’t have the banking relationships, didn’t get the funding,” he said. MCF engaged a law firm specializing in the nonprofit sector to assist those organizations in the second round, Sorge said.

In Green Bay, Cobb said his organization was intentional about engaging with and addressing the needs of organizations serving or led by people of color.

“(Communities of color) require a different level of support and outreach sometimes in a way that allows the dollars to flow to them quicker,” he said. “We’re just always committed to trying to reduce barriers for all of our nonprofits and understand that those barriers can be higher for those entities and individuals who are either leaders of color or organizations that serve individuals that are predominantly people of color. We’re trying to do everything we can to remove those barriers and work to increase representation and leadership in the community.”

Davis of MCF also said she saw an increase in Black families engaged in the formal, usually-white-dominated philanthropy space – a trend she’s noticed the past few years but which accelerated in 2020.

“Philanthropy (in) the Black community has always been there, which we all know. It just may not have been called ‘philanthropy,’ but it’s always been there. And now it’s becoming more mainstream for Black folks to come together … to give back,” she said. “I’ve never worked with so many Black folks before in my career. And that says a lot that they want to give back, particularly with education. That they want to make sure that next generation has the support to get that education.”

The pivot

The BGCDC’s massive mask distribution effort is just one example of many ways nonprofits have shifted to address a whole new set of needs during the pandemic.

The Urban League of Greater Madison (ULGM), for example, launched a parental academy to teach parents to navigate the increasingly complex set of online tools to keep track of their children’s progress in school. Doing so became critical in the pandemic when many parents were directly supervising their children’s day to day learning at home, but ULGM CEO Dr. Ruben Anthony hopes that involvement sticks.

“I know it’s always hard to really connect (schools) with the parents on a consistent basis,” Anthony said. “So, we thought that maybe that would be the best practice for making the parents central, like they should be, to the education of kids.”

It’s an area of service the ULGM wouldn’t normally get into – the organization historically has focused on workforce, housing and youth programming – but like many organizations, ULGM used its existing infrastructure to meet a new need.

“A lot of organizations started fundraising for things that they wouldn’t ordinarily fundraise for,” Sorge said. “For instance, Literacy Network, I think over 70% of their clients, the people that they’re tutoring in English, lost their jobs. So they quickly moved to giving out gas cards, giving out job referrals, giving out grocery cards. So they were gathering money really in a holistic way for the people. They were, in essence, caring for the people that they would ordinarily teach. And I think that you saw quite a bit of that. The Mellowhood Foundation is (another) good example. They’re normally doing a lot of K through 12 educational and mentorship work. And they pivoted to providing fresh food on a weekly basis for seniors, who are isolated at home, and delivering thousands of meals to kids who weren’t in school. You saw a lot of different organizations step up and say, ‘We need to care for our communities. We need to care for our neighborhoods regardless of what our initial mission is. Our mission really is caring for these people in our community.’”

Johnson said the BGCDC was also able to use its existing structure and relationships to fundraise for, acquire and deliver masks and other prevention measures.

“In this particular case we leveraged our advocacy and our platform to bring these resources to the community,” he said. “That’s what we’re going to do. We’ve leveraged some of our private partners with our government partners to pull that off. We’ll assess it, assess the environment as we pivot around our work.”

In addition to new programming, many nonprofits shifted the way they do what they’ve always done, largely through “virtual” programming.

“We had just finished the Boys and Girls Club strategic plan a year before and we had virtual programming as part of our strategic plan,” Johnson said, in order to help families from a wider geographic area access BGCDC educational programs. “The pandemic actually forced us to escalate that work immediately instead of waiting two or three years out to hire somebody, to plan it, to set up committees. It forced our hand to focus on it immediately.”

The pandemic also forced many arts organizations to pivot to online, virtual performances, which had the unexpected impact of bringing in audiences from across the country, Sorge said.

Stronger together

The pandemic also brought organizations together to collaborate in unprecedented ways.

On March 13, 2020, the day Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers announced all schools in the state would close, Johnson of the BGCDC responded by announcing the Dane County COVID Relief Fund to raise money to help feed and provide support for kids who would no longer have the support system they had in the public schools. Madison365 assisted in that effort.

One key difference between that announcement and other BGCDC fundraising efforts: the money would be gathered and distributed through other nonprofit organizations with the connections on the ground to meet the people’s needs directly.

“That’s not something that we typically have done, to raise money for other nonprofits. We’ve done that, since that announcement, maybe three or four other times,” Johnson said. “For example, around housing, instead of us raising money to help families in need I’ve been able to partner with so many different organizations that have been helping Boys and Girls Club families and it’s a beautiful thing that we don’t have to spend our resources to address some of these issues but our partners are helping us support families in need.”

Cobb of the Greater Green Bay Community Foundation said his organization has been able to leverage its position to bring nonprofit leaders together to solve problems.

“One thing that I know that our nonprofits really value is our ability to convene,” Cobb said. “That was something that nonprofits really leaned on to during this time – some of the capacity building workshops that we did in addition to the funding and then just connecting them to as many resources that we were aware of, that we actually had vetted and had trust in as well because our nonprofits trust us.”

In Appleton, a whole new nonprofit organization emerged from a collaborative effort to get COVID-related information into marginalized communities.

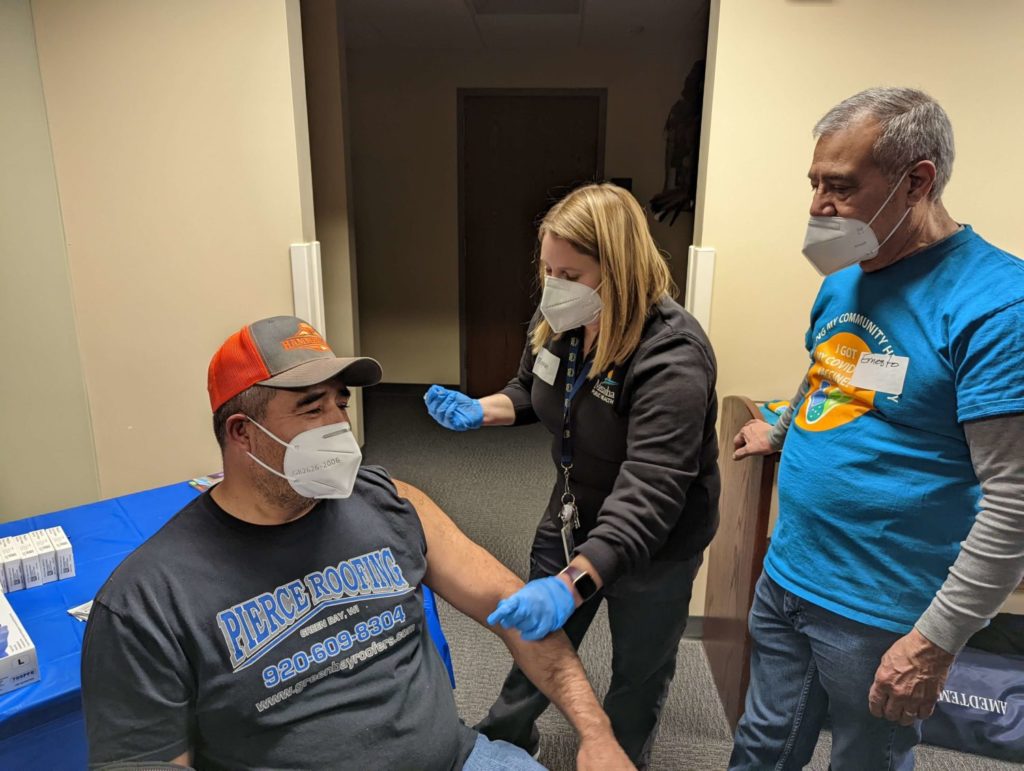

Leaders from several community organizations convened the Multicultural Communications Committee early in the pandemic for the purpose of getting critical information to communities that were being hit hardest by the pandemic, but who might not speak English as a first language or who might not engage much with mainstream media. Meeting regularly over the course of the pandemic forged partnerships and increased capacities to move beyond communications. When vaccines became available, the collaborative group started hosting vaccine clinics – through a culturally competent lens, which meant their clinics have culturally-appropriate snacks, volunteers able to speak many languages, and an open-minded approach to any hesitancy or questions.

What started as a collaborative effort among a number of groups has now become Multicultural Coalition, Inc, a brand new organization that’s applied for 501(c)(3) status and is in the process of hiring staff to tackle more equity issues in housing, education, healthcare access and more.

“I think that synergy, that work that we do together, really reverberates throughout and people listen. I love that fact,” said Ernesto Gonzalez, executive director of Casa Hispana and cofounder and founding board member of MCI. “I think that we are also, through this effort, leveling the playing field so that we don’t have to compete (for funding). We’re saying we all need a piece of this pie and we all deserve it. So we’re working together to benefit from what’s out there. We don’t want to play this game that you want us to enter. … We’ve had this history of the government saying, ‘Play this game and we will award you, and whoever speaks the loudest, or shouts the loudest, or does certain manipulations the best way or, or pats me the best way in the back, or whatever, gets the pie.’ And I think that some people, some very deserving people, get left out because of this game that we play. (Collaboration) is proving to be more successful and getting much better results than what has been the practice.”

Dr. Pam Her, another cofounder and board member of MCI, said the collaboration also allowed for an amplification of those marginalized voices, to the point that the collective group got a sit-down meeting with Department of Health Services Secretary-designee Karen Timberlake that a smaller, single organization might not have gotten.

“I think when she met with us, all of us were there together, and the things that we were sharing were really from one voice,” Her said. “All the things that we were saying were things that were very real and things that we really were struggling with within all of our communities together.”

Her and Gonzalez are both confident that MCI will continue to have an impact well beyond the reach of the pandemic.

“We all have a very, very strong and common shared vision that we want to carry beyond COVID-19. So, we’re excited,” Her said.

Flexibility is the watchword in funding

Perhaps the most seismic shift in the nonprofit sector has been in the manners and methods of funding.

First of all, nonprofits across the board saw an increase in donations early in the pandemic.

“I would say overall individual donors have been amazing. They have stepped up more now than I’ve ever seen, at least from our perspective at Boys and Girls Club,” Johnson said.

Grantmaking institutions like the community foundations saw an immediate need to be more flexible and expeditious in their funding efforts.

“I think funders were very flexible and accommodating,” said Anthony of ULGM. “They knew that things changed with our work and they were very flexible and accommodating and finding out where we needed help. I’m just happy that foundations and supporters continue to support us and be flexible during these times.”

Cobb said the Greater Green Bay Community Foundation brought in about $2.75 million specifically for COVID relief efforts. Whereas the foundation might take months to make funding decisions in a normal grant application process, GGBCF started reviewing applications and getting checks out on a weekly basis.

Making that turnaround time a little faster was something the foundation had been looking at for a while, Cobb said.

“I don’t know if the pandemic hadn’t hit how long that may have taken us to actually get to that point where we were doing that,” he said. “Sometimes you get stuck in doing things the way they are, because it may be just the way you’re used to, and that’s the way the processes are set up.”

Another shift away from business as usual came in the process to apply for foundation funds, Cobb said.

“We always understood that accessing grant dollars should not put additional burdens on nonprofits,” he said. The foundation got most of their funding applications down to a single page, Cobb said, and even started accepting applications that had been originally prepared for other foundations, rather than make nonprofits repeat themselves.

“Nonprofits found that really helpful because they were putting out fires and may not have had two, three, four hours to dedicate to an application,” he said.

Davis said foundations are also more willing to take risk in unprecedented circumstances.

“I think the way that funders look at nonprofits, there are ways that we can be a little more flexible and we have been flexible in some regard and that may stay. It may grow,” she said. “We will take a chance on maybe a newer idea or something out the box, something innovative. I think that will stay. It will at least start a lot of conversations between funders and nonprofits that may not have happened if it had not been for this pandemic.”

Another big shift Cobb has seen is on the other end of the grant cycle: the reporting process.

“One of the things that’s really important for our foundation is making sure we’re good stewards of the dollars that come in the doors and that we push out, but we relaxed some of our final report requirements as well. And so it, and what I mean by that is it became less of a paperwork intensive experience and more of a conversation,” he said. “We found out that those conversations allowed nonprofits to share with us more of their needs to give us better understanding. If you’re just putting pen to paper, you’re specifically answering one question. It doesn’t give an opportunity for you and I to have it back and forth. Those conversations just opened up our eyes and it opened up their understanding of how we might be able to support their wide range of needs.”

Several leaders also said the pandemic called into question the value of fundraising events with trappings like silent auctions.

“Have you ever thought about not having the event, but still making the ask?” Cobb asked, rhetorically. “Recognizing that some people aren’t giving you money because you invite them to an event. They’re giving you money because of your cause.”

“People spend a lot of time on fundraising events, and getting silent auction items, and all these kinds of things. It’s rough,” Sorge said. “I get it because it seems to be an easy way to make some money. But I don’t know, given the fact that we haven’t had those sorts of events, or we have had them in a different format and haven’t needed a lot of the bells and whistles that cost money, take time and don’t bring value.”

Johnson said he’s looking ahead to a post-pandemic world, and cautions against funding the shiny new thing at the expense of more traditional programming.

“The corporations, I would say, seem to be funding more diversity, equity-related issues that are important to the community. But my fear is sometimes when these things happen there’s a shift in terms of funding (away from) legacy programs that have been impactful in our community over the years,” he said. “Sometimes there’s this fight between the traditional work that has been taking place and these new things that are arising. How do you balance and support holistically both of those without pitting groups against each other? I see some of that happening almost every day in Madison.”

The nonprofit workforce

Nonprofit organizations have also run into some of the challenges every other sector has encountered: namely, workforce.

Johnson said the so-called “Great Resignation” – the nationwide trend of people leaving jobs for higher-paying, more fulfilling ones – has hit the nonprofit sector like any other. He notes that the BGCDC has always placed a priority on compensating people well and providing excellent benefits, but still has had to raise its minimum wage from $12 an hour to $15.

“On one hand I know it’s a challenge for a lot of us to be able to do that, but if you want to retain the talent you’ve got to pay people. You’ve got to pay them well,” he said, and that can have reverberations throughout the economy. “The nonprofit sector makes up 13% of the United States workforce. So we’re a huge part of the economic engine. It can’t be ignored.”

Anthony of ULGM said even his organization’s training programs are having trouble recruiting people who now expect to be compensated even for training time.

“It’s a worker’s market where workers are demanding signing bonuses, flexible hours, and just all types of things. And so it’s made it more difficult to get people in the program,” he said.

The nonprofit workforce could leverage the moment to bring in more talent, Sorge said, noting that many people are looking for work that’s not only well-paid, but meaningful.

“Life is short. Whether you’re talking the pandemic, whether you’re faced with issues of equity, whether you’re talking climate change, life is short,” he said. “And what do I want my life to look like? I think the nonprofit field is in some ways, not always, but in some ways able to help people find those answers.”

A cultural shift

The pandemic may have accelerated societal changes that were already underway, and which could change the nonprofit landscape forever.

“I think if it were the pandemic alone, you might see (nonprofit operations return to the way they were), but this is about cultural shift,” Sorge said.

“These things have been gradual, but I think it’s part of the momentum that has been growing over the course of the last decade,” Linfield said. “Frankly, I think high school students today are a lot more aware of what’s going on in the world and are more connected to what’s going on in the world and they were back in the ’80s.”

Linfield said major world events like the murder of George Floyd, combined with technology that allows images of those events to spread quickly, in an environment where things are more or less shut down all conspired to galvanize that cultural shift.

“You have these major events, you’ve got a way to be connected to these major current events, and you’ve got the time to process it,” he said.

“You can’t rationalize away something that you can see on your cell phone an hour later,” Sorge added.

One thing that hasn’t changed is the motivation behind the work.

“This is not nine to five work, this is life work. This is blood work. It has to be something that is done all places in all times and that’s hard,” said Her of MCI in Appleton. “We do it because we love our people, our community, and if we don’t do it, no one else is going to do it.”

Lasting Impacts is funded by a grant from the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. The best way to protect yourself and your community from COVID-19 is to get vaccinated and stay current on boosters. Click here for more infomation.