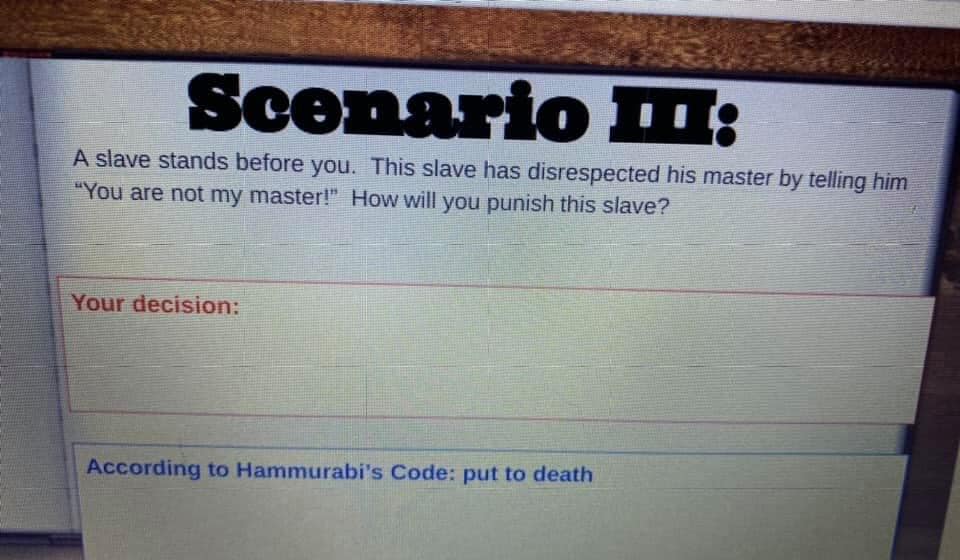

Over the last few years, a number of horrific and racist incidents have occurred in schools throughout the Sun Prairie Area School District (SPASD). In 2018, a middle school tutor was removed for suggesting “low-income” students might ruin education for “good kids.” In 2019, white students were seen wearing blackface at a basketball game. During Black History Month in 2021, sixth graders were asked to speculate how they would “punish” a slave. Later that year, a student of color spoke publicly about how she was being targeted online by her classmates because of her identity.

Many staff, faculty and students of color have expressed concerns about these experiences in the district and how these inequities can be handled.

LaRon Ragsdale was one of the many staff members who worked to make SPASD a more welcoming and equitable place for all students. He started working for the district in 2014 as a coach and worked in the district for nine years, as a coach, youth advocate, dean of students, and athletic director.

Earlier this year, he resigned from the Sun Prairie Area School District (SPASD) after an altercation at a basketball game, and now wishes to share his experiences in the district to help clear his name, explain why he resigned and express his current concerns for students of color in the district.

Ragsdale and other community members, former and current administration and a current high school student talked with Madison365 about their experiences as people of color in the district and Sun Prairie community, and their suggestions about how the school and city can work together to improve equity and inclusion for all students and staff.

The incident

Ragsdale ended his time with SPASD after an altercation at a basketball game between Sun Prairie West and Verona, where an incident got too intense and, he said, didn’t need to.

He felt like that was the best thing for him to do after the game.

“We created a high[ly] intense environment and I don’t think Sun Prairie was used to that,” Ragsdale said. “It was almost like playing in Milwaukee; it was a city environment. There was the dance team, the DJ playing the loud music, everyone was moving around. We had the most staff of color in any of our buildings, but it was a welcoming environment.”

Ragsdale, who was Sun Prairie West athletic director and dean of students at the time, realized that he needed to continue keeping this environment under control, so he readied his staff as the game was coming to an end. Despite his efforts to control the environment, as the game ended, the coaches started to argue on the court.

“We tell the coaches that they need to continue to walk,” Ragsdale added. “Verona was the first team leaving and they kind of slow played the walk which made our coach even more mad, saying that they are celebrating on our court. Mind you, we’ve celebrated on other people’s courts. (That) should have never been an issue.”

The basketball players also began to argue with each other and Ragsdale was threatened by a student as he was trying to de-escalate the situation. The situation was out of his control and that’s when he realized he needed to resign.

“I took my lanyard off, and I set it down because, at that point, my impact was no longer impact,” he said. “My relationships were no longer working. Even the students that were around (the student) were not moving him to put him in a position to be successful. They were almost feeding it fuel. These are the same folks that I help. I’m looking around, these aren’t people that don’t look like me. These are people that look like me. They know the fight that we have in his district. They know what we are seen as and we’re playing right into their hands to be seen as the ignorant Black folks after a basketball game.”

The one regret Ragsdale mentioned having about the incident at the basketball game was not staying one day afterward to talk with the young man who threatened him.

“I’ve seen him since then and I saw the look in his eyes,” Ragsdale said. “He wants to come and have a conversation with me. I want to have a conversation with him. But it can’t happen because of this stuff that’s in between, that is not between us. It’s between the folks that were all around the situation. Him and I had these disagreements before, we’d had these fallouts before and we know what it leads to. It leads to him being better, to me being better, and to us working together, knowing how we got to operate in this world, where we have conflict. That’s probably the only regret out of all is not staying at least one more day so I can have that conversation with him.”

Ragsdale mentioned that it wasn’t the specific basketball incident that made him resign, but a combination of everything that he had to deal with up until that point. He was hurt to see Black community members, whom he’d spent years building relationships with, treat him like he was doing something wrong to them.

“They forgot that together, we built something that got them to where they were and that will hopefully one day excel them past any influence that I had on them,” he said. “All that stuff was out of the window. I was exhausted from my years of being there. I was just at the point where I started to look and say, ‘If I can’t help, I gotta go’. It was just that and I already knew that I was going to end at the end of the year. I was okay with exiting at that time.”

“I felt on the outside a lot”

Ragsdale began working at the district in 2014 as a football coach and felt like he had to prove himself before he was welcomed by other coaches at Sun Prairie East High School.

“The environment was new, it was a lot different. I’m used to being in the inner city,” he said. “I went to school at UW-Stevens Point, so I have some experience with very diverse backgrounds. But in a coaching world, you want to have that comfort, you want to have that welcoming feeling. And at first, I didn’t have it. I had it from the people that I knew that attracted me to the job, like my buddy. But from the overall program, I didn’t feel it right away. I felt on the outside a lot.”

Three years later, along with being a coach, he decided to become a youth advocate. In this role, he was able to talk with students outside of athletics and get to know their issues and concerns. He learned that students were struggling with issues of race and racism within the school building from their peers, teachers and administrators.

“I started seeing students and connecting with them,” he added. “I started seeing their wants, I started seeing that they had these big dreams and desires, but they didn’t have a way to kind of express them. I just started doing my best to build those relationships. In the midst of feeling this uncomfortable with a district or not even a district at the time, I should say with the school building itself…the kids pulled me in even more. And then after that, I was just like, I’m here for a reason. I’m just going to put all that behind me and do what I do best: build relationships and listen to these kids and try to build and create the things that they want to keep them motivated.”

He served as a youth advocate for two years, and connected with a plethora of students. He used his skills to support all of his students and create safe spaces for them outside of the classroom. In discussions with students, he learned what their struggles were and what they felt they needed from their educational environment at the time.

“They wanted more out of their experience in high school. A lot of times when I actually sat down and talked to these students, these were experiences that they were having since they were in elementary school. It just followed them into the high school world,” he said. “They wanted just something more out of education, and then started to see that it was more than what was just happening in those four walls. It was things that were happening in the community, too, that they didn’t have answers to that they wanted guidance around.”

Transition to dean of students

In 2018, Ragsdale transitioned from youth advocate at Sun Prairie East High School to dean of students at Cardinal Heights Middle School. His transition into this position was similar to previous ones; he said he didn’t receive much support or guidance on how to do his job. He recalled hearing conversations from his co-workers stating that he only got the job because he was Black.

In this role, he worked closely with Reggie McGee, who served as the principal of Cardinal Heights from 2017-2019. Before that McGee worked as the associate principal at Sun Prairie High School, which has now become Sun Prairie East, from 2011-2017, and they met during Ragsdale’s time as a youth advocate.

While McGee worked as the associate principal, he was the only Black administrator at the school. He talked with Madison365 about how he felt that students appreciated him being in the building, and how he felt grateful to be able to support them as well. During his second year, students filed many complaints to him about their experiences with race and discrimination from school faculty and their peers.

“My office was like a classroom and we had probably 20 guys in there,” McGee said. “They began to share with me some things that I just never was aware of. It was so ironic because I’m right there in the school with them. Some of them were talking about how they’re being treated by teachers, even one administrator, etc. It was really interesting and we kept those meetings going throughout that year and into the next year.”

McGee recalled how Ragsdale positively impacted all students, regardless of their identities, at both Cardinal Heights and Sun Prairie High School. He mentioned how he was extremely engaged with students to the point where situations didn’t have to escalate to administration involvement.

“I could talk for an hour and a half about LaRon, non-stop,” McGee added. “To me, what I saw was someone who was very transparent about how he maximized some opportunities he got and how he missed some opportunities because they didn’t make the right decision. I feel like that’s how he operated with all the kids.”

As dean of students, “I noticed a lot of lost bodies moving around, and (students) not feeling comfortable in spaces,” Ragsdale added. “Every time it’s a conversation of ‘Well, why aren’t you in class?’ and their response was that their teachers didn’t like them. The students knew I would not let that be the answer. Then it became deeper, they would say, ‘I don’t know this, so they push me in these ways. They say I need to know these things’. It was more like teachers were making them feel bad about being where they were in learning. I noticed that was happening across the board with our Black and Brown students.”

He mentioned how this led to students of color receiving truancy tickets, suspensions and, most notoriously, a rise in students being placed in Individualized Education Program (IEPs). This was a problem, Ragsdale said, because these labels were only placed on students of color because they might have struggled with staying focused in class. These solutions were given to students of color, instead of teachers and administrators working with them to meet them where they are in their educational journey.

“But it was always a tag that was associated with students who were Black and brown,” he added. “I didn’t hear those tags come to those white students that were walking through the hallways, they didn’t get tagged with saying go get IEP, or you have ADHD, like none of that.”

Current student and family experience in SPASD

Naaliyah Currie is currently a junior at Sun Prairie West High School. She met Ragsdale while she was transitioning from seventh to eighth grade at Cardinal Heights Upper Middle School and knew that he would be different from other teachers she had at school.

“I could tell from his relationship with my peers that he was gonna be a teacher that I can really confide in,” Currie said. “I knew it from our first impression of meeting each other, right off the bat. He has helped me a lot with school opportunities, career opportunities.”

Currie also shared horrific experiences she endured as a Black student in the AVID program, which is offered to students in the district from grades seven to 12, designed to increase school-wide learning and performance in students.

Currie’s mother, Nina Stuckey, talked with Madison365 about her experience raising three Black daughters in the district and recalled some of the disrespect she encountered from white teachers as she and her husband fought to protect their children.

“My husband and I had an issue with the AVID teacher,” Stuckey said. “The way she was emailing us, and she was cc’ing Naaliyah in it. The teacher was very rude so I pulled Naaliyah from the program. And I still have the emails to this day.”

Stuckey also advocated for the integrity and fairness Ragsdale presented while he worked in the school district.

“I’ve seen him in many difficult situations where he handled it very, very well,” she added. “He’s very informational. He’s very fair, even when it came to my kids, and they were in the altercations, he never chose sides. He did what was best for both parties. He’s a fair person. He’s very knowledgeable. He’ll help you in any way he can with programs and opportunities that are out here for these babies.”

Currie added a lot of the issues within the Sun Prairie Area School District are because of negative relationships between students and teachers. She talked about how Ragsdale was able to connect with all of his students and how things are different now that he’s gone and reflected on how Ragsdale has been a positive influence over her educational experience in the district.

“I don’t think I would be where I am without LaRon Ragsdale,” Currie said. “I cannot stress it enough. Even the small things, like (experiencing) microaggressions growing up in the community that I grew up in. It’s just the little things for a Black girl to go to school and get bugged about. I shouldn’t have to feel like this in my learning environment.”

Currie also shared some suggestions she has as a current student for how the district can better serve students of color. She feels like the district needs to get rid of its foundation of sending Black boys into the school-to-prison pipeline, and having heavy security guard presence in schools.

“They need to stop setting my peers up for failure,” she said. “They just don’t know how to attend to them and their needs. They also need to focus on better programming for what kids want to do after school. I could talk to many of my peers who don’t know what to do after high school, where they’re going to be, or if they want to attend college as they want to go into the workforce. I think they need to find some type of program for that.”

“Try to make an attempt to understand where students of color are coming from, why they don’t go to class compared to their other peers, and why they don’t feel comfortable at school,” she added. “Do interviews and find out what these students truly need. That’s what I feel needs to happen in SPASD.”

Community members’ current concerns with district and calls for action

Currie and her family are just one example of a Black family’s experience in the Sun Prairie Area School District. Teran Peterson has been an active member of the Sun Prairie community for almost a decade.

She began working with the district as a parent volunteer, then as the Black History Month coordinator, where she and Ragsdale worked together to plan and coordinate Black History Month events. She executed events like soul food dinners, trips, and trivia nights.

Peterson recalled the intensity of a racially insensitive incident at Patrick Marsh Middle School in February 2021, where sixth graders were given a homework assignment where they were asked: “A slave stands before you. This slave has disrespected his master by telling him ‘You are not my master’ How will you punish this slave?”

She also served as the president of the African American Parent Network (AAPN), where she worked with other Black families in the community to support Black and brown students in the district. This incident occurred during her presidency and the organization decided to write a demand letter to the district in response.

“One of those demands was to hire a director of equity,” Peterson said. “There were about 25 demands, they gave us probably 75% of them, but one of the biggest demands was a director of equity. It’s time, obviously, you need it.”

Peterson began serving as a consultant for the district and was in that role for 18 months. She began working with Michael Morgan, the district’s director of systemic equity and inclusion.

“In my original contract, and then my second-year contract, things shifted considerably from what I was doing to what they wanted me to be doing,” she said. “That was part of the reason for the fallout.”

Peterson mentioned that she did a lot of work to get Black history month events established, along with seven other heritage months that the district is supposed to celebrate. She talked more about how there is a huge amount of distrust between communities of color in Sun Prairie and the school district.

“If the district doesn’t like what you have to say, they just stop inviting you to the table and then they just don’t listen,” Peterson said. “There’s a lot of African American families that have pushed for equity, that the district has shut out and shut down and just acts like they don’t exist anymore.”

Peterson feels that there is a lot of work that still needs to be done to support Black and brown students in the district, which is why she is running for a position on the Sun Prairie School Board because she is aware that the governance policies of the board are very restricting.

“I would love to fix the governance policy,” she said. “I think that as of right now, there’s not a ton that the school board can do. Because of how the governance policy is written, their hands are tied on a lot of stuff. That has to be goal number one on the school board. There are now three Black school board members and adding one more would give a majority vote, which I think could be really impactful. I would love to see the governance policy reviewed, because I think the Sun Prairie school board is too hands-off and is allowing things to happen that the community doesn’t know about.”

Peterson said she’s still extremely concerned about students of color and their experiences within the district.

“The students are lacking people that they can trust,” Peterson said. “Losing folks like Ragsdale, myself, and people like that, who the kids flocked to. As soon as any of us had started to put pressure on the district to live up to what they put on paper as their equity statements, we found ourselves working in other places.”

Current Black staff members concerns with district

In July 2022, Ragsdale transitioned from Cardinal Heights to Sun Prairie West High School, where he served as the dean of students and the athletic director. Initially, he wasn’t interested in this position because he would now be working two jobs for the price of one. He noticed that he only received a $13-$15 increase on his bi-weekly paychecks.

In this role, Ragsdale worked closely with Felix Giboney IV, who joined the Cardinal Heights Upper Middle School staff as the dean of students in 2021. Since then, he’s struggled with getting support from the district and feels ostracized as a Black staff member.

“The biggest disappointment is the lack of support they have for the Black men or Black staff, or staff of color in general, as we’re trying to help support students and give advice on experiences and education that we have,” Giboney said. “Being subject matter experts, as Black people, with Black children and students, while constantly being minimized and having our thoughts, ideas and expectations diminished and not even considered. Even just walking throughout the school building and not even being greeted by your counterparts, who don’t look like you, is an issue.”

Giboney said he’s brought up these issues several times to immediate school directors, principal and higher level district officials, and the district’s equity and inclusion professionals. These concerns have still not been addressed.

“There were things last year that I brought up that I thought were true racial concerns, not only to my principal, but also to the director of equity inclusion that were never brought back up for conversation,” Giboney said. “It was all told to take back to the principal. As I’ve always stated, this has been brought up and has not been corrected. How do you expect us as Black staff who feel that we’re being targeted, to take our issues to the people that are targeting us, and then make a change from what they’re doing. That continues to fall on deaf ears.”

Madison365 contacted the Sun Prairie Area School District in regards to these claims. Their response, in an email to Madison365, was:

“While we cannot comment on personnel matters, our district continues to embrace equity, inclusion, and diversity. To that end, Dr. Michael Morgan, Director of Systemic Equity and Inclusion, reinforces, “We encourage students, staff, and parents/ caregivers to bring forth concerns of inequities to the attention of their principals, Site Equity Team Members, or the Department of Systemic Equity and Inclusion for support.”

Ragsdale and others have continued to express their concerns about the safety, well-being and quality of education for students of color in the SPASD. He concluded with current concerns he has for students of color in the district and encourages parents and community members to get involved to see what is happening with their children.

“Pretty much for those folks who actually know me, I just ask that they continue to tell folks who the real LaRon Ragsdale is,” he said. “We have to combat the negative stereotype that comes with it, the negative story that’s been going out there. Everybody knows I give my all, to every single kid. I had the most challenging experience with a student this year where I had to actually do CPR on the student that was not alive, that student was gone. And we happened to bring her back. I bring that up, because this is what I would do for your kid. That’s what I did for years for your kid. I will get in there, and I will make sure that I try my best to bring them life, whether it be metaphorically speaking or in that situation.”

“Do I think that I’m a little worried about the folks that’s there and the students that are coming through?” he questioned. “Yes, I am. Because I think it’s a lot of talk. It’s a lot of smoke and mirrors to these parents. I encourage the parents to get involved and ask more questions, to really get in those school buildings to know what’s going on. Please do not sit on the sidelines anymore. Your kid needs it, now more than ever, because they sell you this thing about what’s happening and it’s not. Our kids aren’t learning, our kids aren’t getting better. Nothing’s changing, it is getting worse. It’s getting worse.”